Tracing the Exile and Tomb of a King: Cheongnyeongpo and Jangneung from “The Man Who Lives With the King”

- Input

- 2026-02-19 13:45:21

- Updated

- 2026-02-19 13:45:21

The ultimate winner at the box office over the Lunar New Year holidays has been the film “The Man Who Lives With the King,” directed by Jang Hang-jun. Released on the 4th, it drew more than 4 million viewers in just two weeks, becoming a runaway hit. The movie turns the tragic story of King Danjong into a bittersweet dramedy filled with both laughter and tears, successfully resonating with audiences across generations. Beyond the powerful performances of Yoo Hae-jin as Eom Heung-do and Park Ji-hoon as King Danjong, what truly captivates viewers is the dazzling scenery of Yeongwol in Gangwon Province. Following the film’s lingering emotions, we walked through Danjong’s time: his place of exile at Cheongnyeongpo, his final residence at Gwanpungheon, the sorrow-laden Jagyuru Pavilion, and finally Jangneung Royal Tomb, where the boy king lies at rest.

■ Cheongnyeongpo, where King Danjong stayed

In the film, Cheongnyeongpo is described as “a remote island so desolate even raccoon dogs would faint from despair.” Eom Heung-do, the village headman from a nearby settlement who runs the place of exile, goes before the authorities with the ambition of feeding his villagers well by managing the exile site and makes the following appeal: “Cheongnyeongpo, an island on land, is filled with sticky humidity in summer and chilled by the icy air rising from the river in winter. It is the perfect place of exile.” As the map he holds up shows, Cheongnyeongpo is encircled on three sides by a river, while behind it rises Yuknyukbong Mountain, once home to tigers, forming a natural fortress. It is a prison in all but name.

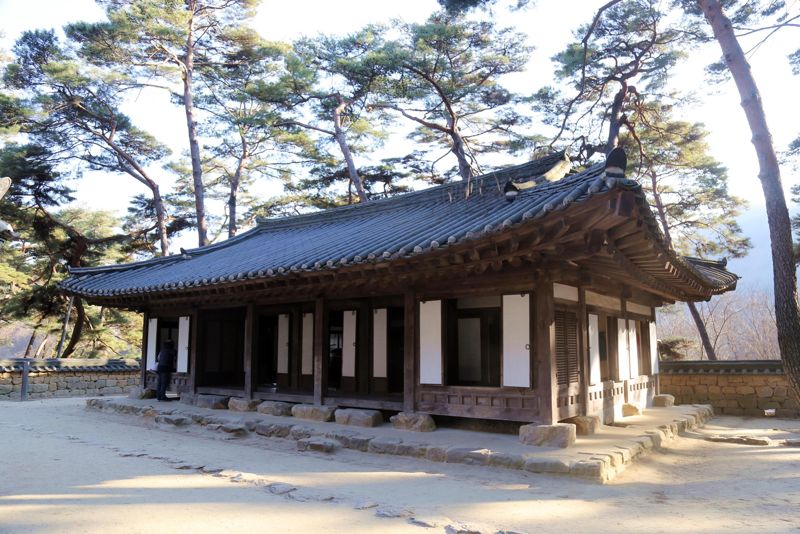

Today, Cheongnyeongpo has been developed as a tourist site, so it is not as rugged as it appears in the movie, but it is still accessible only by boat. From 9 a.m., a small ferry runs across the river (fare 3,000 won). Once you cross and walk into the pine forest, you come upon the royal residence where King Danjong is said to have stayed. This is not an original structure. It was first built in 1975 as part of a restoration project at Cheongnyeongpo, then rebuilt in 2000 to reflect descriptions found in the Seungjeongwon Ilgi, the Diaries of the Royal Secretariat. Around the residence stand the Stele Marking the Former Site of Danmyo Shrine, erected in the reign of King Yeongjo to indicate the location, and the Boundary Prohibition Stele, which once warned commoners not to enter. Both remain in place today.

Walking through the pine grove, you eventually come to the Gwaneumsong Pine, a natural monument estimated to be more than 600 years old. Its name means the pine that “observed” Danjong’s wretched fate and “heard” his sorrowful voice. The tree rises about 30 meters high, and its trunk splits into two large branches near the base. Legend has it that King Danjong would sit astride these branches to pass the time.

Cheongnyeongpo also contains Manghyangtap, a stone tower that, according to tradition, King Danjong built while longing for Hanyang, the old capital. There is also Nosandae, a cliff where he is said to have gazed tearfully toward the place where his mother rested at sunset. In the parking lot overlooking Cheongnyeongpo stands a golden statue showing King Danjong and his consort, Queen Jeongsun, reunited in the heavens.

■ Jangneung, where King Danjong lies at rest

In 1457, at the tender age of seventeen, King Danjong was ultimately put to death by his uncle, Sejo of Joseon. Various records describe his death in different ways. The film “The Man Who Lives With the King” draws on stories found in Yeollyeosilgiseol, a collection of unofficial historical anecdotes, and other unofficial accounts, then adds imagination to depict Danjong asking Eom Heung-do for help and resolutely taking his own life.

Before his execution, King Danjong spent about two more months at Gwanpungheon, the Yeongwol-bu government office, after flooding struck Cheongnyeongpo. A short walk from downtown Yeongwol brings you to the compound: beyond a neat three-gated entrance with tiled roofs stands the quietly dignified Gwanpungheon Pavilion. According to records, Danjong used Gwanpungheon as his sleeping quarters and often went up to Maejukru Pavilion. There he composed poems likening his own situation and grief-stricken heart to the cuckoo, a bird associated with lament. For this reason, later generations began calling the pavilion Jagyuru, meaning “Cuckoo Pavilion.” Even today, the building bears two name plaques: one reading Maejukru and the other Jagyuru, each hanging on a different side.

In the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty, King Danjong’s end is summed up in a single line: “Prince Nosan (Danjong) died in Yeongwol.” That brevity left ample room for countless stories to grow around his death. Despite Sejo of Joseon’s stern warning that “anyone who dares to collect the body will see three generations of his family exterminated,” there was one man who stayed with Danjong to the end: Eom Heung-do, the local headman of Yeongwol. According to unofficial accounts, Eom risked his life to recover the king’s body and secretly buried it deep in the mountains. That hidden grave is believed to be the site of today’s Jangneung Royal Tomb.

Because Jangneung remained a temporary grave for a long time and was only elevated to the status of a royal tomb more than 200 years later, its appearance differs markedly from that of typical Joseon royal tombs. The approach path does not run straight but turns at a right angle midway, and the slope from the flat ground up to the burial mound is quite steep. Another unique feature is Jangpanok, a shrine hall that houses memorial tablets for the loyal retainers who died for King Danjong. There is also a separate Jeongnyeogak Memorial Pavilion honoring the unwavering loyalty of Eom Heung-do, who gathered and buried Danjong’s remains, adding further historical meaning to the site.

jsm64@fnnews.com Jeong Soon-min Reporter