[The 8cm Judicial Barrier, Part 1] The paradox of the first year of judicial support: Wheelchairs stopped at the courtroom door

- Input

- 2026-02-09 15:49:19

- Updated

- 2026-02-09 15:49:19

The Judiciary has introduced new regulations this year to support persons with disabilities, older adults, and pregnant women. Measures that once amounted to mere “consideration” for people in vulnerable positions in the justice system have now been elevated into binding internal rules that the Judiciary has pledged to follow. Building on this, the Supreme Court of Korea has declared this year the “first year of strengthening access to justice,” and Chief Justice Cho Hee-dae of the Supreme Court of Korea has vowed, "We will continue to expand judicial support for socially vulnerable groups." Yet the threshold of the courts remains high. From physical obstacles inside courtrooms to a lack of human support and complex institutional barriers, hurdles persist at every stage. Over three installments, this series will closely examine how court facilities and budgets, the effectiveness of dedicated support systems, and the accessibility of complex written judgments continue to exclude people in vulnerable positions in the justice system. [Editor’s note]

[Financial News] "The biggest problem is that it is still practically difficult for a wheelchair to enter many courtrooms. In reality, there are quite a few places where there is not enough space or a proper ramp from the entrance route to the defendant’s seat," said Kim Do-yoon, a public defender specializing in court-appointed cases who has represented many clients with disabilities.

"Seating arrangements for parties and witnesses that take into account people with mobility impairments, and the installation of Braille guidance blocks for people with visual impairments, are still far from sufficient," noted Lee Seung-heon, secretary-general of the Coalition for the Elimination of Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities.

The criminal standard courtroom at the Seoul Central District Court, the largest court in the country, which this reporter visited on the 9th, illustrated these concerns vividly. Most courtrooms are located on the third floor or higher, so visitors must take an elevator from the main entrance level. Even then, the elevators are so narrow that once a single powered wheelchair enters, there is virtually no room left. The layout effectively forces persons with disabilities to feel self-conscious under the gaze of other users.

Conditions inside the courtroom were similar. The public gallery had 28 seats, but there were only two spaces for wheelchair users, one on each side of the entrance.

The public gallery and the party seating were separated by a rail-type barrier and an 8cm level difference. As a result, anyone moving to the defendant’s seat had to use a ramp. For older adults using a cane, it appeared they would inevitably need assistance from a companion to go up and down the ramp safely.

■ Official "guidelines," but an 8cm step in reality

At the beginning of the year, the Supreme Court of Korea issued “Regulations on Judicial Access and Judicial Support for Persons with Disabilities, Older Adults, Pregnant Women, etc.” The core elements are: specifying detailed standards for wheelchair routes inside courtrooms and for installing party and witness seating for persons with disabilities; establishing a basis for providing sign language interpretation, Braille materials, and judicial support staff (assistants); and committing to provide judgments and litigation documents in forms that are easier for people in vulnerable positions in the justice system to understand.

On the ground, however, the situation diverges significantly from the Supreme Court of Korea’s declarations from the very first step. In particular, “facility accessibility,” meaning physical access to courtrooms, is widely recognized as the starting line for participation in judicial proceedings, yet there has been little tangible change.

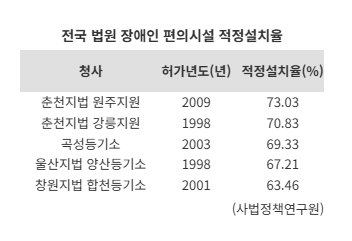

Removing restrictions on access to judicial facilities for persons with disabilities is a long-standing and repeatedly raised task. According to a study published last year by the Judicial Policy Research Institute (JPRI), 18 out of 58 court buildings nationwide (31 percent) in 2023 fell short of the average rate of proper installation of accessibility facilities for state and local government institutions, which stands at 80.7 percent.

In an additional survey of 20 courts, JPRI found that the proper installation rates for detailed items such as the width and slope of main entrance routes and the condition of floor finishes had actually declined compared with previous surveys. Only 13 court buildings met the legal standard for the slope at the entrance, which must not exceed 3.18 degrees.

This suggests that, despite its mission to uphold constitutional values, the court system is in practice neglecting Article 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea, which provides that all citizens are equal before the law and shall not be discriminated against.

There are, however, some positive signs of improvement. The criminal courtrooms at the Seoul Eastern District Court, which was newly built in 2017 and received a high rating for disability-related facilities, have completely eliminated internal level differences, allowing both wheelchair users and other pedestrians to move freely without restrictions.

■ A smaller budget than seven years ago, and “equality before the law” still out of reach

The problem is that such barrier-free courtrooms—facilities adapted so that persons with disabilities and older adults can move comfortably—have not spread nationwide because of budget constraints.

In practice, the Judiciary’s budget for “expanding and improving accessibility facilities for persons with disabilities and others” was 997 million won in 2019 and 937 million won in 2020, but then dropped sharply to around 526 million won annually from 2021 through last year. This year, the related budget has increased again to 721 million won, but that is still only about 72 percent of the level seven years ago. Even this figure combines the budget for improving courthouse environments to enhance the public’s access to justice.

On the ground, many say that more active budget allocation is essential. A judge at a court in the greater Seoul area remarked, "Because our courtrooms are structurally narrow, there are many cases where wheelchair users simply cannot enter at all," adding, "Ultimately, the issue of courtroom accessibility is something that can be resolved through funding." The judge went on, "At a minimum, there should be at least one barrier-free courtroom nationwide," and stressed, "We need a substantial expansion of the budget for facility accessibility and a proactive, forward-looking review of these issues."

scottchoi15@fnnews.com Choi Eun-sol and Jung Kyung-soo Reporter