[Editorial] Next Week's Korea-China Summit Must Untangle the Complicated Bilateral Relationship

- Input

- 2025-12-30 19:16:10

- Updated

- 2025-12-30 19:16:10

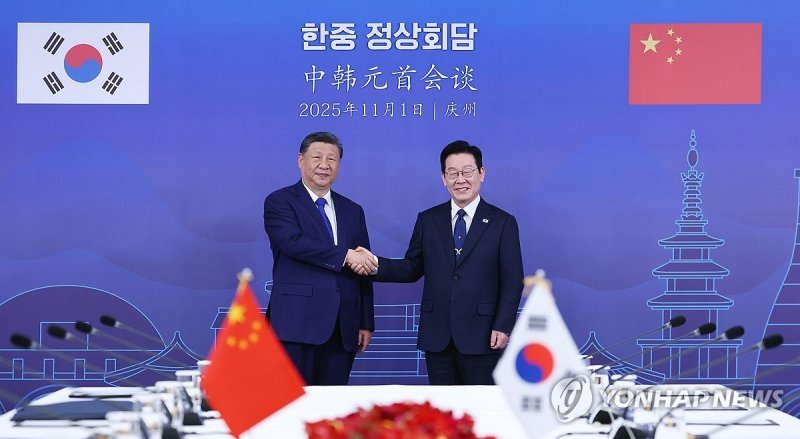

The Korea-China summit comes just two months after the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Gyeongju last November. The short interval between meetings suggests signs of change in the recent relationship between the two countries.

Historically, Korea-China summits have tended to reflect the foreign policy priorities of both governments and the state of U.S.-China relations. During the early Park Geun-hye administration, the two countries strengthened their Strategic Cooperative Partnership between South Korea and China, but summits were effectively suspended after the deployment of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD). Although summits resumed under President Moon Jae-in, no tangible results were achieved amid escalating U.S.-China tensions. During the Yoon Suk Yeol administration, bilateral relations cooled, but under the current government, there are signs of improvement.

Currently, there are numerous urgent and sensitive political and diplomatic issues between Korea and China. The most sensitive topic is the nuclear issue involving the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK). The DPRK has advanced its Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and tactical nuclear capabilities, approaching the so-called 'red line.' While South Korea’s pursuit of a nuclear submarine is a self-defensive measure to deter the DPRK’s nuclear threat, China may interpret it as a signal of regional arms competition. The government must clearly state that the purpose of nuclear submarine discussions is solely to deter the DPRK’s nuclear threat and maintain regional stability, thereby preventing unnecessary misunderstandings.

The issue of structures in the West Sea is also a pressing matter that cannot be postponed. China’s installation of structures near the provisional measures zone resembles its 'incremental sovereignty expansion' strategy repeatedly seen in the South China Sea. Such actions are not isolated incidents but matters that threaten regional maritime order and international norms. It is essential to firmly present non-negotiable principles for safeguarding sovereignty and to persuade China based on these principles.

Unlike the diplomatic and security fields, where immediate agreements are difficult, tangible results in the economic sector—directly affecting livelihoods—are even more crucial. Trade, which surged after the 2015 Korea-China Free Trade Agreement (FTA), has peaked and is now declining, with the trade deficit with China becoming entrenched. China’s technological level has advanced beyond the stage of importing intermediate goods from Korea for final assembly. As it is now difficult to achieve results in the Chinese market by selling only goods, Korea must expand the scope of economic cooperation to services and investment markets to seek new growth opportunities.

The meeting between the Korean and Chinese leaders is no longer just a bilateral event; it is a major development that affects the entire Northeast Asian order and U.S.-China relations. Regular communication between the two leaders can serve as a minimum safeguard to prevent conflicts over issues such as the DPRK nuclear problem, supply chain restructuring, and maritime order from escalating.

The government must firmly uphold the national interest on core issues such as the DPRK nuclear threat and maritime order, while demonstrating practical diplomacy by achieving tangible results in trade, investment, and services. The success of the Korea-China summit will depend on the government’s ability to balance principle with pragmatism in its diplomatic decisions and execution.