"Working 13 Hours a Day, Earning 4 Million Won a Month... 10,000 Cafes in Seoul Alone"—Cafés Become the Graveyard of the Self-Employed

- Input

- 2025-12-05 13:50:21

- Updated

- 2025-12-05 13:50:21

[The Financial News] "If I could start over, I would do anything but open a café."

Go Jang-soo, who runs a café in one of Seoul’s densely populated areas, shared this sentiment. There was no need for further explanation. On a weekday morning, his café was empty. More than 50 competing cafés were located near his shop.

The New York Times (NYT) published an article on the 3rd (local time) titled "South Korea Has a Coffee Shop Problem," examining the nation’s love for coffee and the overheated state of the café market.

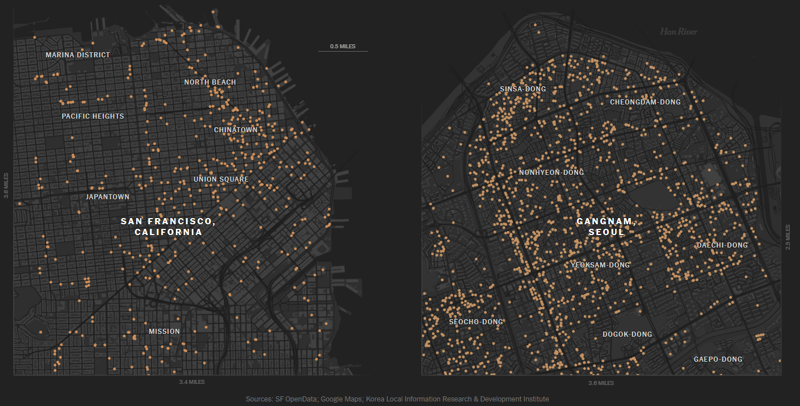

Gangnam District in Seoul Has More Cafés Than San Francisco

NYT noted that Go’s experience is far from unique in Korea. The article added that Seoul’s café density rivals that of Paris.

Citing statistics, the article introduced Koreans’ love for coffee by stating, "Koreans now drink coffee more often than rice."

NYT explained that many Koreans, seeking to escape the repetitive routine of working from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., dream of making money by opening their own café.

This trend quickly spread across Korea, with thousands of new coffee shops opening every year.

The article also pointed out that as many cafés close as open, highlighting Go’s case.

NYT reported that Sillim-dong was labeled as part of Gangnam District rather than Gwanak District, and when Go opened his café there in 2016, competition was not as fierce. At that time, there were only two other cafés nearby.

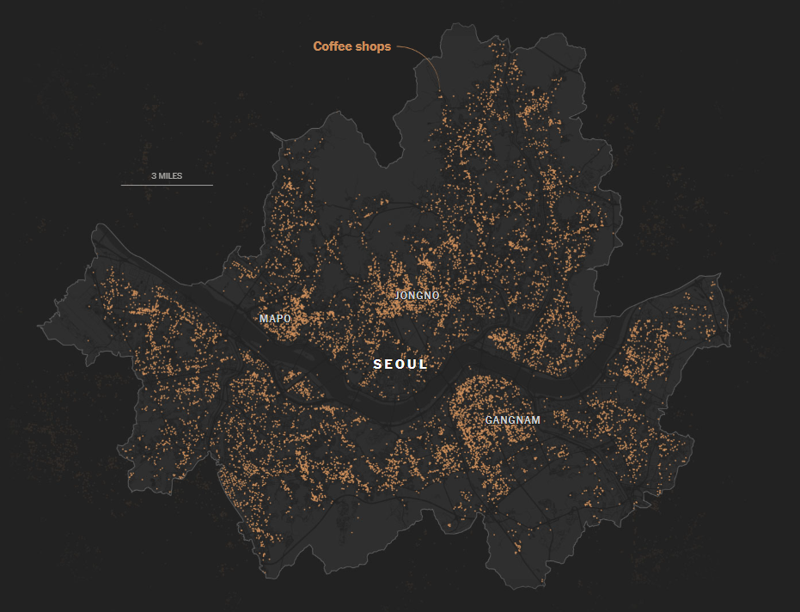

As the café boom spread across Korea, the number of cafés nationwide doubled over the past six years. Out of Korea’s population of 51 million, there are now 80,000 cafés, with 10,000 located in Seoul alone, especially concentrated in Gangnam District, Jongno District, and Mapo District.

NYT compared the situation in San Francisco, known for its strong coffee culture, to Seoul’s Gangnam District. The article described how, in Seoul, especially in Gangnam, cafés line both sides of the street like a parade.

Café owners in Korea told NYT that the café boom was fueled by people seeking alternatives in a tough job market and by the image of coffee as a trendy beverage, which encouraged many to start their own businesses.

"Don’t Open a Café to Get Rich"

NYT, describing this situation, warned, "No one knows how long they can survive."

NYT further explained that coffee was introduced to Korea in the late 19th century as a luxury item, but after the Korean War, instant coffee powder brought by the U.S. military made it accessible to everyone. Korea began producing its own instant coffee mixes, which remain popular today.

After Starbucks entered Korea in the late 1990s, the Iced Americano—known in Korean as 'A-A'—became the country’s unofficial national beverage.

Recently, cafés in Korea have come to mean more than just a place to drink coffee.

NYT reported, "Many people live in small apartments with their families, making it difficult to invite guests over. Cafés provide spaces for couples to spend time after dinner, for old friends to chat, and for students to study."

The article also pointed out that this café culture has led to misconceptions about running a café.

NYT noted, "In Korea, a stagnant job market and harsh office culture lead many to view opening their own shop as a path to independence. Cafés are cheaper to start than bars or restaurants and require no special certification. Social media, showing crowds flocking to popular cafés, fuels the illusion that running a café is an easy way to make money."

Go, who is also the head of the National Cafe Owners Cooperative, said, "People see long lines in front of other cafés and think running a café is simple. But the work is tough and the profits are low."

Sunwook Choi, a café consultant who has helped open more than 1,000 cafés, said, "Most people who jump into the business are not prepared. They have never run a coffee shop, and at best, their experience is as a part-time barista." He added, "Many owners earn about 4 million won a month, which is just above minimum wage, and that’s after working more than 13 hours a day."

Choi also pointed out, "Many coffee shops close within one or two years, right after their first lease expires. The lifespan of coffee shops is getting shorter."

Amid this bleak market, NYT focused on YouTube videos that discourage people from opening cafés. One such example is Kwon Sung-joon, winner of Netflix’s cooking competition show Culinary Class Wars. After reflecting on his own failed café business on the show, Kwon advised viewers not to start a café.

The NYT article closes with Go’s somewhat painful advice, delivered from his empty café.

"A café is not a place to get rich. It’s simply a place to go and have a cup of coffee."

y27k@fnnews.com Seo Yoon-kyung Reporter