The Ghost of 'Price Control': Is the Delivery App Cap Justified [Hyun Min-seok's Fair Play]

- Input

- 2025-07-19 07:00:00

- Updated

- 2025-07-19 07:00:00

[Financial News] As the new government takes office, its determination to establish fairness in the platform economy is being emphasized daily through the media. Among these, the 'delivery app commission cap', promoted under the pretext of alleviating the burden on small business owners, is emerging as the most promising policy task with great public support. This straightforward plan to legally limit the commissions of dominant platforms appears at first glance to be a righteous solution to protect economic underdogs.

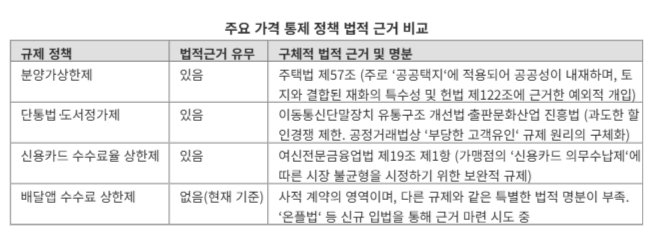

However, attempts to artificially control market prices have historically resulted in numerous side effects and have been evaluated as a 'high-risk strategy'. Looking back at the history of similar price control policies, we have clearly witnessed the unintended consequences in all cases, such as the pre-sale price cap, the single price law, the fixed book price system, and the credit card commission cap. The bigger issue is that while other past price regulation policies had at least minimal legal and institutional justification, the delivery app commission cap is particularly weak in its legal basis. Is this policy a reasonable regulation that our society can bear, or is it an unconstitutional 'price control' ghost that defies market principles?

We must critically distinguish how the legal foundations of seemingly similar regulations differ fundamentally. Comparing the legal bases of major price control policies reveals their differences clearly, as shown in the following table.

As seen in the table, other regulations have their specific legal justifications. The pre-sale price cap is mainly limited to 'public land' created for public purposes by the state, inherently embedding public interest in the project itself. Housing, combined with land, possesses the unique characteristic of being a resource whose supply is inherently limited. This is precisely why Article 122 of the Constitution allows the state to impose special restrictions for the efficient use of national land. The single price law or fixed book price system, rather than regulating the price of services itself, aims to maintain market order by preventing 'unfair customer inducement' under the Fair Trade Act, by limiting excessive discount competition or subsidy discrimination.

The most frequently compared credit card commission cap is also a complementary measure possible because the state mandates all merchants to accept credit cards under Article 19, Paragraph 1 of the Specialized Credit Finance Business Act. Since the state imposes this obligation by law, there arises a policy justification to protect the weakened bargaining power of merchants resulting from it.

However, in the case of delivery apps, all these premises are absent. No law forces restaurant owners to use a specific delivery app, and usage is entirely within the realm of 'private autonomy'. If a platform abuses its dominant market position, it can already be sufficiently regulated under the current Fair Trade Act. Yet, the attempt to impose a special regulation of 'price cap' on the specific industry of delivery apps alone is difficult to find legal fairness and justification. This is an unconstitutional idea that poses a significant risk of infringing on the freedom of price determination, which is the essential content of private contracts, as it constitutes discrimination without rational reason.

More concerning than the weak legal justification is the clear economic side effects this policy will bring. As proven in numerous past cases, artificial price control inevitably triggers a 'balloon effect', transferring the burden to other weak links in the ecosystem rather than alleviating economic pressure.

Platform companies will seek other revenue sources to compensate for the reduction in commission income bound by law. The easiest way is to pass the cost onto consumers. The competitive product of 'free delivery' may disappear, and new costs such as 'platform usage fees' or 'service charges' may be introduced. Additionally, they may further pressure restaurants to purchase advertising products or restructure the compensation system for delivery riders to reduce costs. Ultimately, the benefits of commission reduction will be offset by increases in other costs, and the damage will be passed on to consumers, other businesses, and riders. This is akin to salting the well to dry up the spring of innovation.

The role of the government is not to be a 'planner' who directly determines market prices. It should faithfully play the role of a 'competent gardener' who helps market participants compete freely within fair rules. A gardener only waters and removes weeds so that the flowers and trees in the garden can grow well, without forcibly determining the color of the flowers or the shape of the trees. Strengthening transparency by requiring platforms to clearly separate and disclose all commission items, strictly punishing obvious unfair practices that disadvantage small business owners by unfairly using transactional status, and establishing effective dispute resolution procedures are what the government should do.

It is irresponsible to summon the ghost of price control, which shakes the foundation of the market economy, to gain short-term political support. Instead of succumbing to the 'temptation of short-term prescriptions' like the commission cap with obvious side effects, we hope the new government will choose the wisdom of 'fundamental improvement' that fosters a dynamic market while creating a fair competitive environment, even if it takes time.